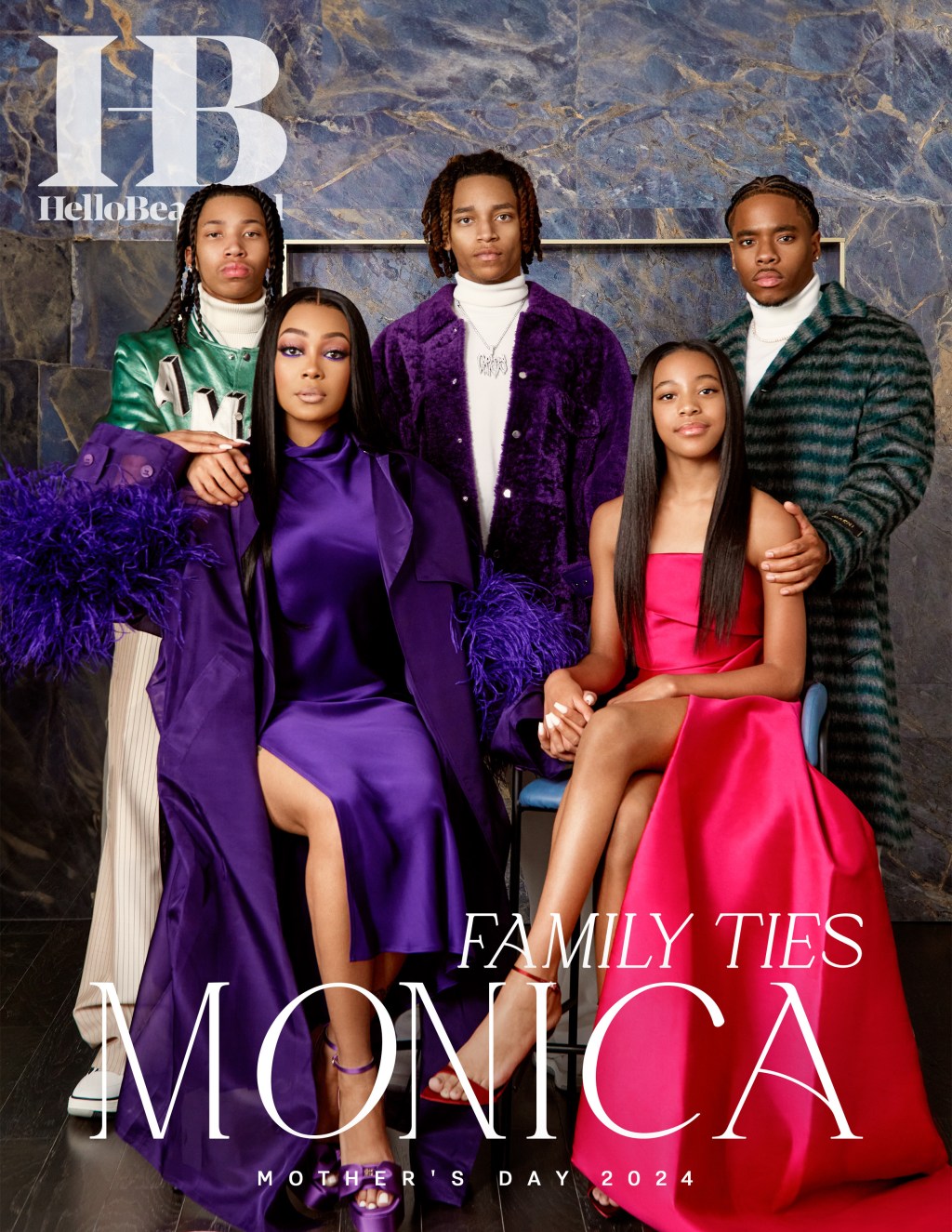

An unidentified woman (not the subject of this story) in Boston’s “Combat Zone” in the 1970s. (Source: Spencer Grant / Getty)

In the waning hours of a tranquil summer night, a young woman holds the dawn at bay with sheer grit. She has work to do. That is all that’s on her mind as she expertly navigates the shadows in stilettos. Breasts and head held high, eyes determined, and lips parted, she zeroes in on the task at hand—feeding herself, her children and her pimp. Like so many other nights, she and the young women like her line up in Boston’s notorious “Combat Zone,” where sex and drugs thrive in the shadows of the city’s monuments and state buildings. The year is 1976 — America’s bicentennial. But while the country’s “City On A Hill” is drawing thousands in to celebrate two centuries of ‘freedom,’ for this young woman, the definition of the term is far more complicated. Her truths are among the city’s darkest, where lust and violence walk hand in hand with pleasure and the almighty dollar. But it’s hardly a deterrent for her and her fellow sisters of the streets. She’s a hustler and a businesswoman, and sex is her trade.

Forty-two years later, she sits down with me to share the good, the bad and the in-betweens of her experiences. After more than four decades of holding tightly to her secrets, she releases her truths. She’s open about her life as a sex worker, a life that is not only dark and dangerous but also empowering.

“Some of us were forced into it, while some of us turned tricks by choice, addicted to the money, excitement and glamour of it all,” Juanda C* tells me in a voice filled with excitement when we speak one Monday evening after her long day at work. Now a mother, grandmother, author and reverend, she requested that her name be changed to protect the identities of her family members.

“We were beautiful and broken,” Juanda says. “A secret society of women made up of women from all walks of life. We knew each other’s names and we frequented the same clubs and after hours. We shared the necessary information, what were the popular vices of the tricks, any crazy we needed to look out for. It was industry information, and this was all in a night’s work.”

Though Juanda has long left the streets behind, the aftershocks still linger, and the residue of pain clings to her like a well-worn coat. She’s ready to tell her story not only to unburden herself of the secrets of her past but also in the hopes that women like her, both young and old, will know that they are not alone. There is a life after the “the life,” and she is a living, breathing testimony.

“I’ve talked to certain people about certain episodes. I have 3 daughters and 2 granddaughters and, since I can remember, I’ve protected them from all of this. When they were growing up, they didn’t know. It wasn’t until just recently, when my 20-year-old granddaughter simply said to me, ‘mom-mom, what happened to you? Tell me your story’ that I thought maybe they were finally old enough to know my truth.”

Juanda was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1956. Her mother’s first-born, she was just 15 years younger than her. It meant that they not only grew up together but that there was tension in that process. Her childhood was a lot of things – easy wasn’t one of them.

“I was 14 when I left my mother’s house and I didn’t go back,” she tells me. “She was with someone at that time who was an active heroin addict. He was abusive—verbally, physically and emotionally. He was a mess and all I wanted to do was get the hell away from them. This guy was so abusive, his energy was bad and it was concentrated on me because I was the oldest and I was verbal about it. He was stealing my shit and shooting dope in front of me when I was 11 years old. I had already been traumatized by the world … before I even walked out the door.”

And walk out the door she did – still a child, with no one to help her. She didn’t know much, but she knew she wanted out.

“He was beating me one day and I had just had enough. I just left,” she says matter-of-factly. “And I went to the streets. There was nowhere else to go. When a judge came back and told me my bond was a dollar—that I could literally go home for a dollar—I said, ‘No thanks. I’m not going home.’”

For Juanda, the devil she didn’t know offered freedom.

“I started out boosting,” she tells me. But it wasn’t long before she was “dancing on barroom tables, gathering the attention of patrons and receiving money.” Within a few short years, she would become an exotic dancer, and from there, graduate to selling sex for money. She learned the power of sex early and by the time she was 17, she was a professional.

Juanda’s experience in this context is not unlike so many other girls like her. According to a recent study conducted by the Beazley Institute for Health Law and Policy at Loyola University Chicago, many girls who find themselves in the sex trade come from abusive homes and are runaways. By some estimates, up to 80 percent of sex trafficking victims have been a part of the child welfare system.

Moreover, she recalls her pimps less as the ostentatious, volatile “Hollywood” types, but more as part of an adopted “family” unit.

“We didn’t sleep around with men in the community,” she says. “We had our men, our boyfriends and our pimps, and we didn’t blur those lines. The streets were a job.”

What Juanda describes is a system run by men who are often referred to as “Romeo Pimps” by law enforcement and journalists alike.

“Individuals that consider themselves gentlemen of leisure really don’t use their hands to get their point across,” one former pimp referred to by the name “Terry” told the Los Angeles Daily Times. “They do it by finesse, by speaking to a woman, telling her exactly what you want her to know, what you want her to do.”

It’s a game of manipulation, experts say. Especially for women who grew up without stable male figures in their lives. In comes a Romeo Pimp, who treats them with a perceived amount of respect, while simultaneously manipulating them into the life.

Juanda’s pimps, along with her customers, fed her growing addiction to a seductive limelight that bathed Boston’s underbelly in its glow. She was making money every night, whereas other girls her age, trapped in a punitive, anti-Black system had nothing to their names. She was able to come and go as she pleased, as long as by nightfall, she was on the streets turning tricks.

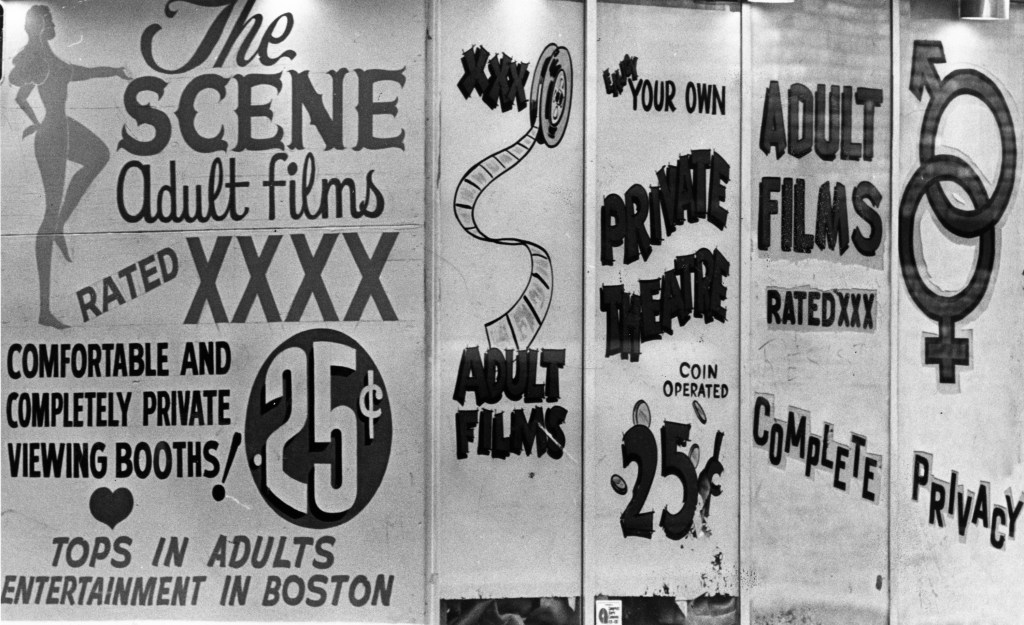

(Signs in Boston’s “Combat Zone,” 1976) Source: Boston Globe / Getty

The geographic region was part of Boston’s notorious “Combat Zone,” known for its adult entertainment – strip clubs, peep shows and adult novelty stores. Moreover, it was known around the country for its prolific prostitution. It began in the 1960s after city officials moved the red light district from Scollay Square as part of a massive urban renewal campaign. The denizens relocated from there to Washington Street, where the cost of living was much lower, and nightlife was already booming.

But when the city began to ease up on obscenity laws in the 1970s, the movie theaters began playing adult movies and prostitution began picking up steam, especially on Juanda’s old haunt, LaGrange Street. So prevalent were the hookers and adult businesses that even the politicians famously seemed to take a relaxed approach, for the most part.

A 1998 Boston Globe piece notes:

In the mid-’70s, prostitution in the Zone was so uninhibited that police reported rush-hour traffic snarled by streetwalkers reaching inside cars to fondle male motorists. Dozens of sex industry enterprises thrived. In the alleys, in the bars, around the corner and up the stairs, Boston’s 7-acre tenderloin was sizzling. The police turned a blind eye. Business boomed. In 1976, the Wall Street Journal called the Zone “a sexual Disneyland.”

(“Boston’s “Combat Zone”) Source: Boston Globe / Getty

For Juanda and the woman like her, their youth, just as their bodies, was a commodity.

In 1975 alone, nearly 100 girls under the age of 17 were arrested for prostitution in the Combat Zone. Dozens more were arrested but ended up charged with being a Child in Need of Services. Still, the young prostitutes were often the ones to take the charges in the place of the Johns.

“We were young and we were on a timeline because we knew we didn’t want to be hustling at 25,” she says.

I stop on this point, asking her what happens to women after 25, assuming that it was a question of ambition or simply growing tired of the lifestyle. She pauses thoughtfully before offering me an explanation.

“There was this OG pimp – although looking back now he was probably about 35, maybe 40 — and he would tell me every day: ‘don’t nothing depreciate faster than an old whore.’ There are some people who never come out of it – they die there. Their children go in. It’s like a spirit that can affect generations.”

“And what happens to those women?” I ask her.

“The ones I know of are dead,” she says, matter-of-factly, her voice completely devoid of emotion. “They’re dead or nondescript. No one knows where they are.”

It’s a shift in the conversation that, while maybe not unexpected, is drastic. But Juanda is quick to remind me that when the life was “fun, it was really fun. But then you flip it to the other side and it’s dark. It’s disgusting. It’s degrading. We had our money, yes, but we also knew this life could very well kill us.”

In her recollections, the danger was always there – a silent partner in the lifestyle she was living.

“You don’t want to remember the nights you got beat up or they stole your money or you were violated,” she tells me, speaking in general terms. “No one could rescue you. Who were you going to tell?”

She recalls one instance where everyone was on edge:

“We had a guy who would catch the girls. He would rob the girl and the trick at gunpoint, and then rape the girls. Violently. And this was something we knew about, but again, who could we tell that to?”

“I had another experience when I got in the car and the guy put a gun to my head to demand I give him head. Thank God, when I went down the police came up and stopped him, because there’s no telling what could have happened.”

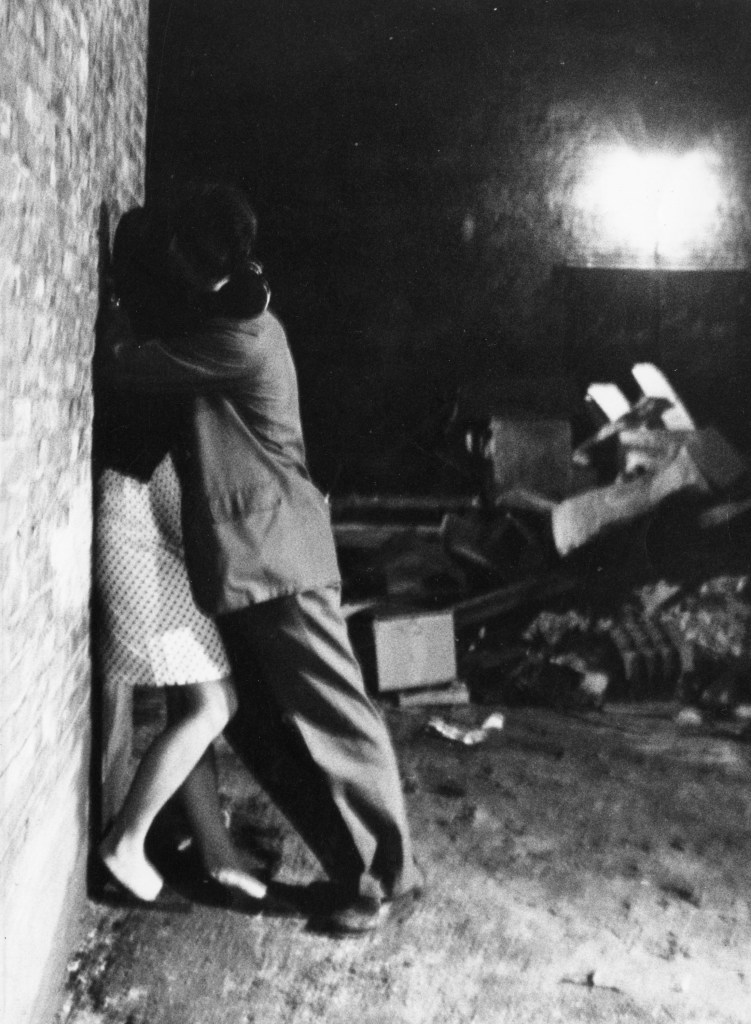

(The shadow of a stripper in the Combat Zone in Boston, 1973. ) Source: Boston Globe / Getty

It was in this environment that Juanda learned she pregnant with her first child. She was 17-years-old and in a relationship with her first love.

“He was someone I met through the juvenile system. He was my age … and he came pre-me going into the sex trade. He happened to be very much a criminal; he still is. Even back then he was very involved with the law,” she tells me.

For a moment, there’s a wistful quality to her memory of two people in love, living in the tornado of their own Bonnie and Clyde romance. It was a partnership that, while toxic, offered her an acceptance she had never known. They were young, wild and free of secrets, living completely on their own terms.

“I married him when he was in jail and then got into a whole other piece with him. Just holding onto that life of when I was this gangster with him, I was this hustler,” she says.

But like so many storms, the tumult and danger were too strong for her to withstand. Of the end of their romance, she simply says: “his life finally broke me.”

Three weeks after giving birth, her daughter’s father was sentenced to ten years in prison.

“I looked at the judge and I said, I’m 17 with a 3-week old. What the hell am I gonna do? I didn’t wanna deal with life. I didn’t wanna deal with kids. I gave her to my mother and I left to start really hustling.”

For a year, Juanda tried her hand at dancing in LA’s party scene. But the city’s lights and lure of prosperity belied a dark world of serial killers like the “Hillside Strangler” and the “Skid Row Slasher,” all of whom killed multiple women and had suburban housewives and sex workers shook alike.

“In the 70s, they were finding women’s bodies in canyons and all types of crazy stuff,” she remarks, clearly aware that for a single black sex worker, her future there was far from stable.

Boston, she decided, in spite of all of its demons, was still the preferable option. She knew that devil now and could navigate his streets with ease and familiarity. She was a woman now, and one with a growing ambition.

(Continued on next page)